Why Do We Believe Organ Donation Conspiracies?

Organs aren’t “harvested” or “kept on ice.” But countering mistrust and misinformation in the Black community isn’t easy.

This article is part of “On Borrowed Time” a series by Anissa Durham that examines the people, policies, and systems that hurt or help Black patients in need of an organ transplant.

By Anissa Durham

When doctors told Andrew Jones his heart was failing, everything he thought he knew about organ donation was wrong — and he’s not alone.

Thousands of Americans are dying for an organ transplant, especially Black Americans, who face higher-than-average rates of illnesses that lead to organ transplants. But misinformation, medical mistrust, and low health literacy rates have left many Black folks with the wrong information.

“I never understood how the organ donation process works,” Jones, 35, says. “I seriously thought they had organs on ice in like a beef block somewhere in the basement, and they would just thaw them out when someone needed a heart transplant.”

That was until he contracted strep throat in college. The once-healthy and athletic New Britain, Connecticut, resident soon found himself fighting for his life. The infection developed into viral myocarditis and ate away at his heart tissue. By 22, he was in heart failure. Within weeks of his diagnosis, he was listed for a heart transplant.

To keep him alive, doctors placed a defibrillator in his upper left chest. But he continued to deteriorate. In 2015, Jones underwent his first open-heart surgery. Doctors implanted a left ventricular assist device — a mechanical pump that helped his heart circulate blood. The LVAD moved him down on the wait list.

RELATED: The Cruelest Kind of Heartbreak

Jones’ story illustrates a larger problem: many Americans don’t fully understand how the organ transplant system works until they find themselves or a loved one in need of a kidney, liver, or heart. In a YouGov survey of 1,000 U.S. adults, 41% of registered donors said they signed up because they knew someone who needed a transplant. Non-donors, meanwhile, cited distrust of the medical system, personal health conditions, and a general lack of knowledge about organ donation as reasons why they decided not to register.

Recent Reports Exacerbate Fear of Organ Donation

But confusion isn’t the only problem. Mistrust of the system itself, particularly after reporting about scandals at a handful of the nonprofits that help people get organs, has made some Americans even more hesitant to be a donor.

Organ procurement organizations are federally designated nonprofits responsible for recovering organs from deceased donors. There are 54 OPOs nationwide and their work includes educating the public about organ donation, identifying organ donors, and working with agencies to match organs with transplant recipients. But recent investigations into unsafe practices at OPOS have led thousands of Americans to remove themselves from the organ donor registry.

A New York Times investigation found that “some OPOs are aggressively pursuing circulatory death donors and pushing families toward surgery.” The Times found 55 medical workers in 19 states who witnessed at least one unsettling case of donation after circulatory death.

“We have to tear down our current medical system,” says Glenn Ellis, a Philadelphia-based medical ethicist. The difference between ethics and the law, he explains, is that ethics is what you should do, and the law is what you are required to do.

Glenn Ellis, a medical ethicist, at his home in Philadelphia, PA, on Wednesday August 20 2025. Credit: Hannah Yoon for Word In Black

“It’s impossible to have an ethical medical system when you got all these silos out there,” Ellis says. “None of these folks involved have been trained ethically. They’ve been trained clinically, medically, and legally.”

He points to the case of Adriana Smith, a Black woman from Georgia who was kept on life support because she was pregnant and past the six-week abortion ban period. Her brain-dead body was forced to keep the fetus alive for three months until the baby could live outside of her womb.

There’s no record that Adriana’s organs were procured for transplantation. But it’s impossible to ignore how these ethical challenges lead to more medical mistrust, Ellis says.

The Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network, which includes OPOs, has an ethics committee that regularly develops white papers on ethical issues regarding organ recovery and transplantation. But in late July, Health and Human Services Secretary Robert F. Kennedy Jr. threatened to close several OPOs after a Health Resources and Services Administration investigation found 351 cases where organ donation was authorized but not completed due to some form of alleged negligence.

“Our findings show that hospitals allowed the organ procurement process to begin when patients showed signs of life, and this is horrifying,” Kennedy said in a statement. “The organ procurement organizations that coordinate access to transplants will be held accountable. The entire system must be fixed to ensure that every potential donor’s life is treated with the sanctity it deserves.”

In September, HHS decertified the Life Alliance Organ Recovery Agency, a division of the University of Miami Health System. It is the first OPO closed due to unsafe practices, poor training, and chronic underperformance.

The Union Between Misinformation and Low Health Literacy

As trust erodes, many Americans feel even less equipped to make choices about their health, especially around organ donation and the transplant process.

A lack of health literacy compounds the problem. According to the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, personal health literacy is the ability to find, understand, and use information and services to make health-related decisions for oneself and others. Yet, nine out of 10 adults struggle with it.

Low health literacy is linked to higher hospitalization rates, greater use of emergency care, decreased use of preventive services, poorer health, and higher mortality. The statistics get more grim when broken down by race and ethnicity, socioeconomic status, and insurance coverage. In a Milken Institute report, 41% of Hispanic adults, 25% of American Indian/ Alaska Native adults, and 24 % of Black Americans scored below basic in health literacy.

Ultimately, Jones received a heart transplant in 2016. He admits that his experience forced his family to ask difficult questions, including those that revolved around how much time he had left: What’s the average wait time for a heart transplant? For someone so young, what is to be expected? How long will a heart transplant last?

“This was an entirely new world for all of us,” he says. “Organ donation conversations, they’re just not had in Black and Brown households.”

Andrew Jones poses for a portrait in at Stanley Quarter Park in New Britain, Connecticut on September 18, 2025. Credit: Shahrzad Rasekh for Word In Black

The Double-Edged Sword of Social Media

With the rise of social media and other web-based platforms, it’s never been easier to get health information — or to get it wrong. Brittney Smith, senior manager of district partnerships at the News Literacy Project, says social media inundates Americans with dangerous miracle cures, conspiracy theories, and home remedies.

Platforms like TikTok and Facebook are ideal for false and misleading information to thrive and even dominate. Smith, a former high school science teacher, says her students would often repeat the infamous organ donation conspiracy theory: doctors will not work as hard to save a patient in the emergency room if providers know they are a registered organ donor.

Terms like “organ harvesting” or “body parts black market” circulate on social media, in pop culture, and sometimes in news stories, reinforcing conspiracy theories that doctors will let you die so they can sell your kidneys or liver.

Conspiracy theories “can make people [believe] organ donation is bad,” she says. “In times when we don’t have a lot of information or something is mysterious, we come up with these oversimplified explanations. But there is factual information out there about organ donation.”

RELATED: He’s a Legendary Transplant Surgeon. At 88, His Work Isn’t Done

How to Debunk Conspiracy Theories

In the early 2000s, Ieesha Johnson began working for a California-based OPO, educating nurses and doctors at local hospitals about the organ donation process. But after a move to Maryland, she shifted her focus to the community, conducting outreach in high schools and churches.

Johnson soon noticed low donor registration rates in Baltimore’s predominantly Black 21215 zip code. To figure out why, she held focus groups that identified three barriers: medical mistrust, a lack of education, and concerns about organ allocation.

In 2016, Johnson, now the director of community outreach for Infinite Legacy, an OPO that serves Maryland and Washington, D.C., launched The Decision Project. The campaign combines health education with tangible support: food drops, scholarships, and after-school programs. There’s also an annual block party offering free health screenings, food, clothing, backpacks, and school supplies. Within five years, the donor registration increased by 500%.

“We stay because we want to take away those myths and misconceptions in our community,” she says. “We know that our communities are at stake. If people can start trusting Infinite Legacy, they can probably start trusting the hospital.”

Ieesha Johnson photographed in her office at Infinite Legacy in Baltimore, Maryland on August 13, 2025. Credit: Shernay Willams for Word In Black

That focus on trust led to some creative partnerships. Two years ago, when Johnson’s friend Charlotte Butler-Strickland, principal at Hart Middle School in Washington, D.C., told her about a colleague who needed a kidney transplant. Students were creating videos to help their teacher get a kidney, but they were also repeating myths and misinformation.

The two friends quickly developed a program to educate seventh graders about the organ donation process. Over six lessons throughout the spring semester, Infinite Legacy invites organ transplant recipients, transplant surgeons, and living donors to speak directly with students. Butler-Strickland says the students have, in turn, educated their parents and family members. This year marks the second iteration of the program, and she plans to keep it going.

“Even the adults in the building who had mistrust about transplants are open to it. And the beauty of it all, Mr. Kennedy got a kidney transplant,” she says. “Students learned a lot. The experience has changed their perspective.”

The Earlier the Education, The Better

Programs like these are reshaping how folks view organ donation on a local level, but federal efforts to tackle the nation’s broader health literacy crisis are needed, too.

Every decade, HHS updates its Healthy People initiative to improve national health and reduce disease. The latest version, Healthy People 2030, places new emphasis on health literacy — aiming to increase the number of adults whose health care providers checked their understanding, reduce reports of poor communication with health care providers, and generally increase health literacy.

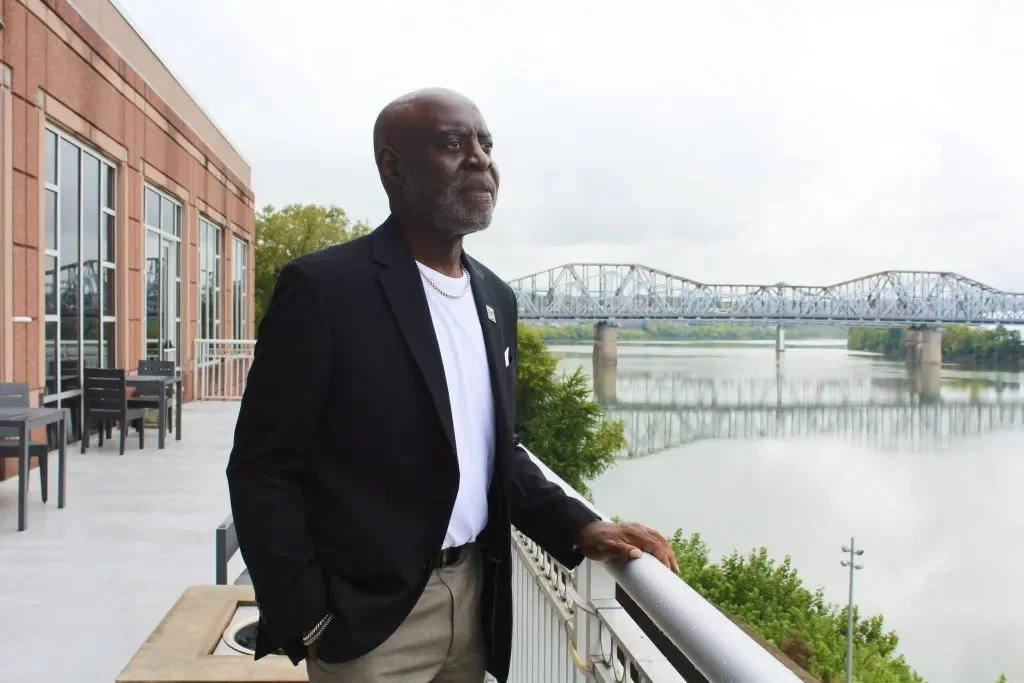

“Organ donors come from the community, not the hospital,” says Atlanta resident Bobby Howard, the director of the multicultural donation education program at Lifelink Georgia. And if we want more organ donors, early exposure and consistent education are key.

Howard knows first-hand what it’s like to have your life saved by an organ donor. In the 1990s, he was diagnosed with end-stage renal failure. After seven months on dialysis, he got a kidney transplant on Oct. 25, 1994, an experience that led him to work in the organ procurement and transplantation field.

Bobby Howard, 61, a kidney transplant recipient, photographed on September 24, 2025. Credit: Anissa Durham for Word In Black

When he first started, it was a fight to discuss organ donation with Black folks because mistrust was so deeply seated. While it’s still a challenge, he says, the conversation is much easier thanks to exposure to successful transplant recipients like himself..

But Howard emphasizes you can’t talk about donation without addressing the economic and social realities that keep many Black folks unhealthy in the first place. About 80% of health outcomes are driven by these conditions, things like income, education, housing, health care access, and community environments.

“The overall concern and issue within the African American community is the lack of education about overall health care,” Howard says. “A lot of people don’t have access. They have the corner store. We’re relying on inadequate food to feed the community.”

As a result, Black Americans have higher than average rates of chronic diseases such as high blood pressure, diabetes, and obesity — the very illnesses that often lead to a need for new organs.

“Always remember that if we sit by and do absolutely nothing, zero lives will be saved,” Howard says.

For Tamika Samuel, 42, education and awareness came too late. Over a decade, she watched her mom, Etta, endure multiple heart attacks and a mild stroke before eventually being diagnosed with congestive heart failure and listed for a heart transplant.

Originally from the U.S. Virgin Islands, Samuel says conversations about health — and especially about organ donation and transplantation — are rare in her Caribbean community.

However, when Etta’s heart was failing, Samuel and her siblings were forced to learn about the process on the fly. To make things more challenging, her dad died during open-heart surgery for clogged arteries in June 2022.

“I lectured my father endlessly about his eating habits,” she says. “He just didn’t make time to exercise the discipline needed to create a better lifestyle and a better relationship with food.”

Etta Samuels holds a family photo, which includes Tamika Samuel (yellow dress) and her late husband, Neville Samuels (second from right), at her home in Powder Springs, Georgia, August 29, 2025. Credit: Alyssa Pointer for Word In black

His death made the thought of her mom going through a heart transplant surgery even more frightening.

“Obviously, being Black American means being concerned about being in the hospital at any given point for anything,” Samuel says. But Etta received a heart transplant on March 27, 2025.

Is it Ethical for OPOs to Educate the Community?

Ellis, the medical ethicist, questions whether it’s ethical to leave education about organ donation and transplantation up to OPOs.

At the end of the day, Ellis says, the education OPOs provide comes down to marketing and a business model. Oftentimes, the first interaction a family has with an OPO is when their brain-dead or circulatory-dead loved one is approached for organ allocation. This is problematic, Ellis says, because it’s an extremely vulnerable and delicate time for families.

Instead, organ donation and transplantation should be discussed during annual check-ups, he says — long before a patient needs one or a family is approached to proceed with donation.

“People don’t even know what decisions they are making, because a lot of that mistrust will go into the grave with these folks,” Ellis says. “If there were higher levels of literacy, people would be able to say ‘I’m not taking this with me,’ or ‘absolutely not.’ But it’s a gray area.”